From a Bulgarian factory to Sudanese militias, the FRANCE 24 Observers team reveals how European-made ammunition ended up on the Sudanese battlefield despite a European Union embargo on sending weapons to this war-torn country. This five-part investigation starts in the middle of the desert, with a series of videos filmed last November by Sudanese fighters.

The videos, posted to X and Facebook on November 21, 2024, show Sudanese militants in camouflage poring over piles of documents that include identity papers, photos and religious images. The militants are from the Joint Forces, a coalition of armed groups that are active in the western Sudanese region of Darfur. This group provides support to the Sudanese army in its fight against the rebel group the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

The militants who are filming these videos have just captured a convoy of several vehicles in the middle of the desert. In the images, they seem confused.

At one point, one of the militants shown in the video examines a passport.

“What country is this?” he asks, in Zaghawa, a language spoken in Darfur. Then he picks up an image of a Catholic saint and says, “Look, they are Jews working for an international organisation,” clearly confusing the two religions.

“These people will do anything, even come to die here in Sudan,” he continues. “They’ve come to support the RSF.” The militant claims many times that the owners of the passports, who have allegedly been wounded or captured by his unit, are “mercenaries”. There are no prisoners or bodies shown in the footage.

On several occasions in the video, you can see two of the passports that the Sudanese militants are examining. This allows us to answer at least one of the militant’s questions: both passports belong to Colombian nationals.

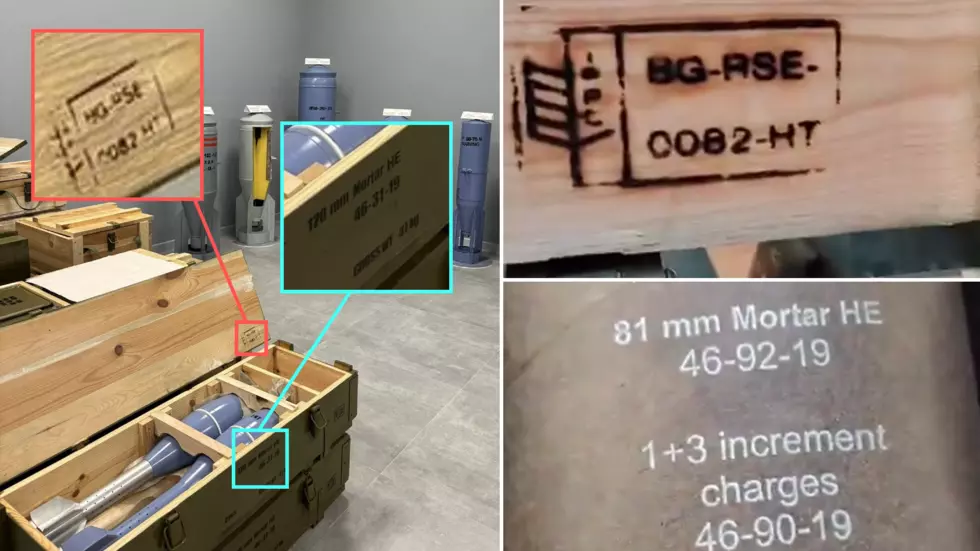

Two large wooden crates marked with an orange diamond-shaped label depicting an explosion, the international symbol for explosives, also appear in the video. They are filled with cylinders and labelled, in English, “81 mm Mortars HE”.

‘All that was for the Rapid Support Forces!’

As the video continues, one of the militants points to the ammunition.

“That’s for the Janjaweeds [Editor’s note: a name given to fighters in the Rapid Support Forces]. Mohammed bin Zayed sent them [Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan is the president of the United Arab Emirates].”

The man then pounds his fist on a vehicle that has apparently also been captured.

“The Emirates sent that, too,” he says.

A few hours after these videos first appeared online, the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), one of the armed groups that is part of the Joint Forces, posted a statement on Facebook about the weapons that had been seized. Through these statements, we were able to learn a bit more about why two foreign nationals were traversing the Darfur desert with this ammunition.

“In the desert region on the border between Sudan, Libya and Chad, the Joint Forces thwarted a massive attempt at weapons smuggling to the terrorist militia the Rapid Support Forces (RSF),” reads a statement posted on the group’s Facebook page.

The SLM also reveals that the “mercenaries” were found to be carrying money from the UAE.

The SLM doesn’t say anything about the fates of the Colombian men suspected to be mercenaries— whether they have been captured, killed or wounded.

The FRANCE 24 Observers team was able to discover much more about where the weapons seized by the Joint Forces came from, thanks to the footage filmed and posted online. It turns out that the weapons are from the European Union. They were manufactured in Bulgaria and bought by an Emirati company. Before being intercepted by the Joint Forces in Sudan, the convoy transporting the weapons passed through eastern Libya, a zone that is controlled by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, an ally of the UAE.

The UAE has been accused in the past by UN experts of providing the Rapid Support Forces with military and financial aid to preserve its own geopolitical and economic interests in the region. However, Emirati authorities have always denied these accusations.

European weapons made in Bulgaria

The labels stamped on the cylindrical containers indicate they hold mortar shells.

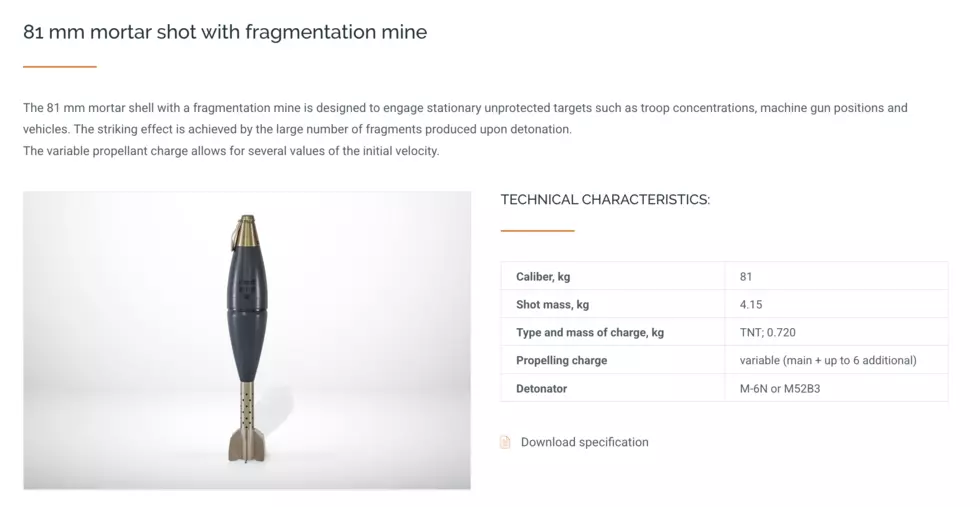

“These weapons are very common in every conflict, and certainly extremely common in all of the conflicts that have taken place in Sudan for decades,” says Mike Lewis, a specialist in armed conflicts and former member of the United Nations panel of experts on Sudan. “Mortar bombs [or shells] are explosives that are fired from a short cylinder, normally along a high parabola trajectory. So it goes up quite a long way and then descends.”

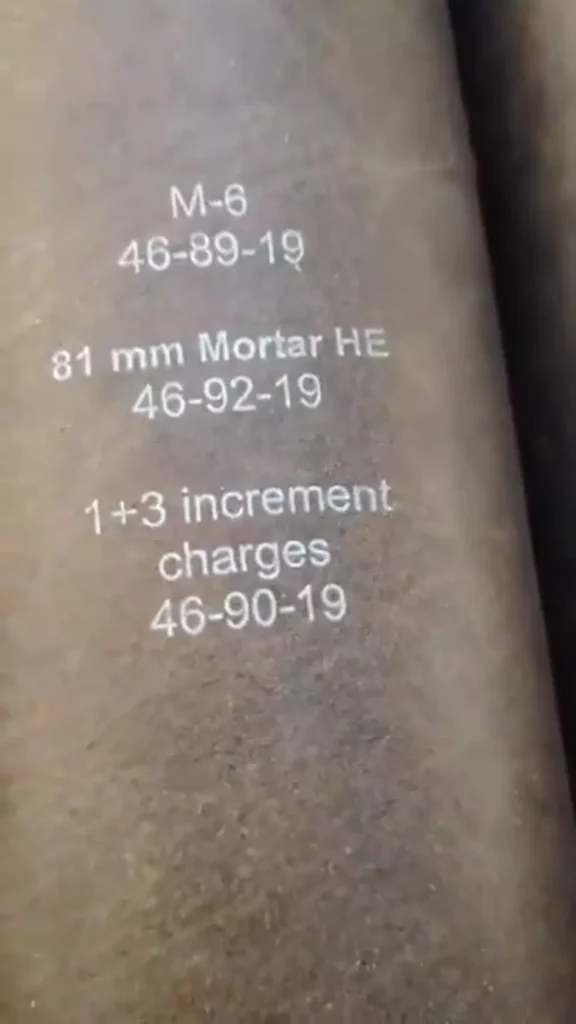

The footage filmed on November 21 shows a man opening one of the crates containing the mortar shells and zooming in on a label that reads: “BG-RSE-0082-HT”.

The letters, which are seared into the wooden crate, are an ISPM-15 code that is mandatory for goods transported in wood packaging. The first two letters of the code indicate the country of origin: “BG” stands for Bulgaria.

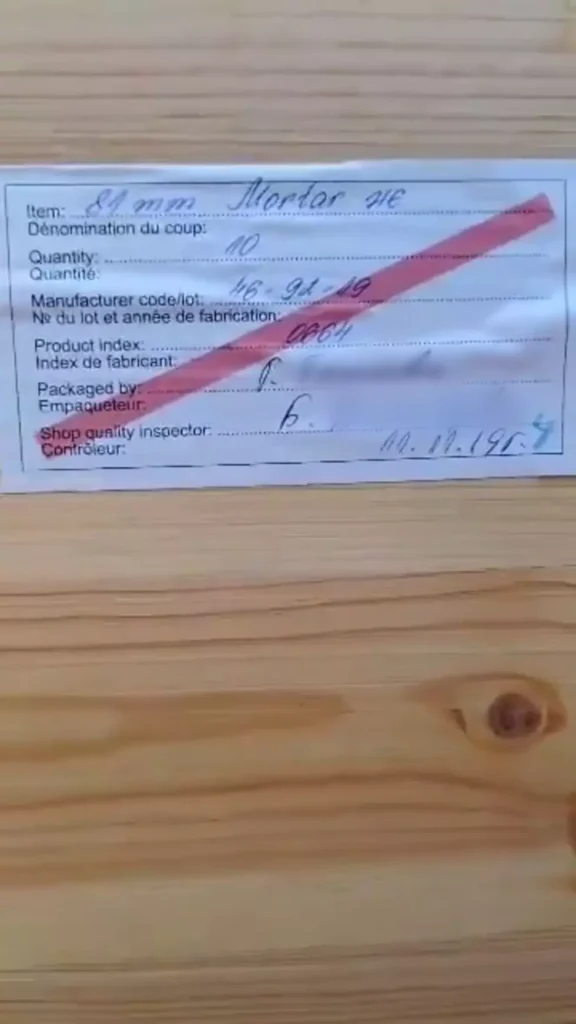

There is another clue pointing to Bulgaria. While the label on the box is written in French and English, it bears two names written in Cyrillic that presumably belong to workers in the factory where the weapons were manufactured. Bulgarian is written in Cyrillic and both names are common for women in Bulgaria.

These labels provide clues not only on the composition of the ammunition, but also on their country of origin and their manufacturer.

M-6 indicates a type of detonator that launches ammunition, while “81 mm Mortar HE” describes the ammunition, which measures 81 mm and is highly explosive. The “1+3 increment charges” refers to the number of propellant charges frequently found on this type of ammunition.

Each of these components has a 6-digit number that enables them to be traced. And all the numbers in the videos start with “46”. The FRANCE 24 Observers team spoke to a weapons expert who explained that in Bulgaria’s identification system, a number beginning with “46” indicates that the weapons were manufactured by the Bulgarian company Dunarit. He said that the number “19”, the final two digits of the number, indicate that the weapons were manufactured in 2019. This can be cross-referenced with the label on the crate.

Dunarit’s website indicates that the Bulgarian company does indeed manufacture highly explosive 81 mm mortar shells.

Moreover, when we looked at the company’s social media accounts, we saw photos of mortar shells packed into a wooden crate, just like the ones that appear in the video filmed in Sudan. Both crates shown in Dunarit’s photos and the ones that appear in the footage have the code ISPM-15 stamped on them. The number is written in the same format as those on the ammunition found in Sudan.

Dunarit’s CEO doesn’t deny that mortar shells were manufactured by his company

Our team contacted the CEO of Dunarit, Petar Petrov, who doesn’t deny that these mortar shells were manufactured by his company. We spoke to him on the phone after we had earlier shown him screen grabs from the videos:

The regulations on this kind of thing are very strict in Bulgaria. According to my information, everything in this contract [Editor’s note: the contract that allowed for the weapons to be exported] was done according to the rules.

He said that he found it difficult to believe that mortar shells manufactured by his company were found in Sudan and contested the veracity of the videos filmed on November 21.

Bombs that violate the European Union’s embargo on Sudan

But how did these bombs manufactured in Bulgaria, a country belonging to the European Union, end up in a supply convoy going to Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces?

Since 1994, the European Union, of which Bulgaria is a member state, has had a total embargo on exporting weapons to Sudan.

“The sale, supply, transfer or export of arms and related material of all types, including weapons and ammunition, … to Sudan by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Member States… shall be prohibited whether originating or not in their territories,” the latest embargo states.

Nicolas Marsh is a specialist in arms exportation at the Peace Research Institute in Oslo:

There is an European Union arms embargo on Sudan that definitely covers this kind of equipment. There is a very clear EU policy. There are some exceptions, but I can’t see how a transfer that was going on to Sudan could possibly be covered by those exceptions. It is definitely a violation of the European Union policy.

Bulgaria has strongly rejected claims these weapons were sent directly from Bulgaria to Sudan.

The Interministerial Commission on Export Control, the Bulgarian authority that approves arms exportations, said by email that the weapons were sold with “suitable authorisation” to a “government of a country on which no sanctions are imposed.” They “denied categorically that the relevant Bulgarian authorities delivered export permits to Sudan” for these munitions.

As we continued our investigation, we did indeed establish that Dunarit’s mortar shells were not exported directly to Sudan. They were, however, sold to the International Golden Group — an Emirati company known for transfering weapons to zones under international embargo.

Continue on to read the other parts of our investigation: