Haunting accounts of torture in newly found detention centre lead to calls for an investigation into what experts say could be among the worst atrocities of Sudan’s civil war

- Evidence of torture found as detention centre and mass grave discovered outside Khartoum

Lying between the makeshift graves is a mattress, a large bloodstain visible in the midday sun. A name is scrawled in Arabic on its ragged fabric: Mohammed Adam.

Who was Adam? Had he ended up here, in a bleak corner of a remote military installation in Sudan’s Khartoum state? Had his body been stretchered on the mattress from the detention centre nearby and dumped into one of hundreds of unmarked graves?

Almost two years into Sudan’s catastrophic civil war, Adam’s likely demise reflects the unanswered questions being asked across the country. The conflict is characterised by unrecorded killings, enforced disappearances, by families searching vainly for lost loved ones. No one knows exactly how many have died.

Similarly it is a conflict contaminated by myriad war crimes. Few episodes may prove to be more egregious than what evolved within the amber-bricked building several hundred metres from where Adam’s mattress was found.

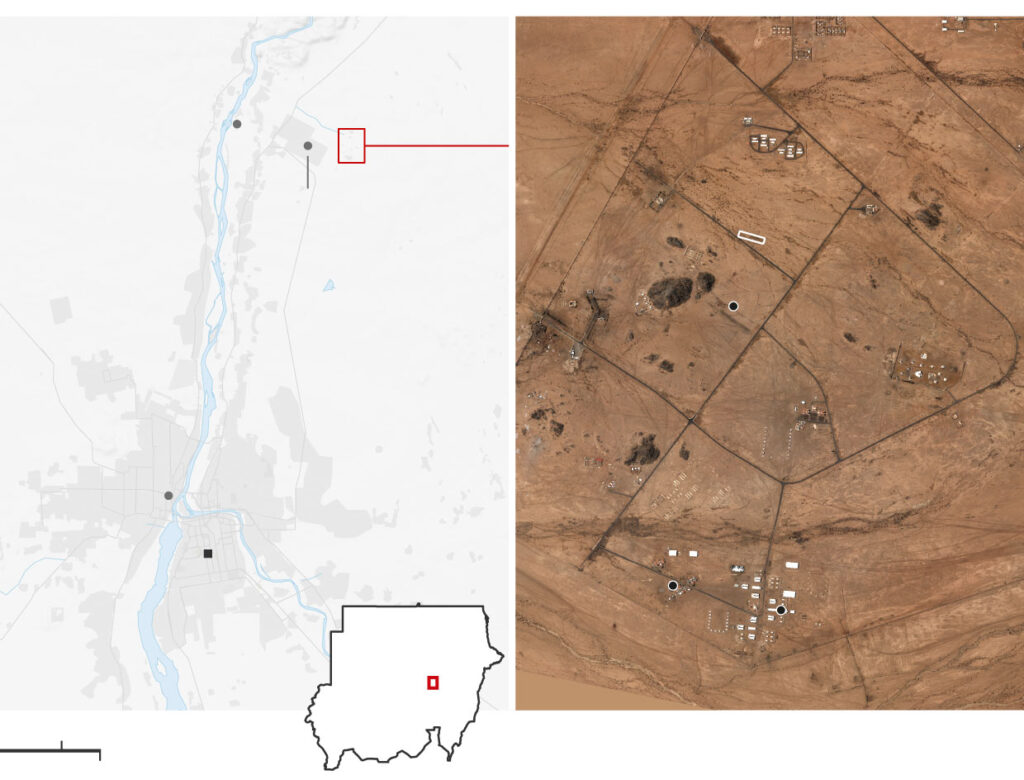

The building housed an apparent torture centre under the command of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). As calls start for an investigation into the magnitude of what unfolded inside, attempts to identify the bodies within hundreds of unmarked graves nearby will hopefully begin.

Possible clues to who may lie in the hastily dug graves might be found in an A3-size notebook found by the Guardian on the grubby floor of the torture centre. On each page, carefully written in ballpoint pen, are listed 34 names in Arabic. Some have been crossed out.

Whoever the detainees were, they suffered. They were beaten repeatedly, and daily life was unswervingly horrific. Scores were rammed into rooms no bigger than a squash court. Survivors describe being wedged so tightly they could only sit with knees tucked under their chin.

A corner of the room doubled as a toilet. When the Guardian visits, the air is thick with flies; the stench unbearable. Graffiti covers the walls. Some pleads for mercy. One message reads: “Here you will die.”

Behind a mesh door with manacles swinging from it are several windowless rooms 2 metres square that doubled as torture chambers, say Sudanese military officers.

According to statements given to doctors, detainees were repeatedly thrashed with wooden sticks by RSF guards. Others were shot at point-blank range.

In an area used by the RSF guards, bullet holes have scarred the ceiling.

Those not tortured to death faced gradual starvation. Speaking on a military base in the city of Shendi, Dr Hosham al-Shekh says detainees have revealed that they received a modest cup of lentil soup, about 200ml, a day.

Such sustenance yielded about 10% of the calories required to maintain body weight. Swiftly, they wasted away.

Physically broken, the detainees were also psychologically shattered. Trapped in a twilight world with no hope of exercise – no space to move – many of them were rendered almost mute by the trauma of their existence.

Atrocity experts say the size of the makeshift burial site is unprecedented in terms of the ongoing Sudanese war. So far, nothing has come close to matching its magnitude.

Military sources who have inspected the site say each corpse is commemorated by a breeze block that serves as a headstone. A number of the graves – their mounds of earth conspicuously bigger than others – are framed by at least 10 breeze blocks.

Jean-Baptiste Gallopin, of Human Rights Watch, urged the Sudanese military to grant “unhindered access” to independent monitors, including the UN, to collect evidence.

The experiences of detainees also reflect the wider war. From the start, Sudan’s conflict was marked by ethnically motivated attacks and detainees reported being racially abused in the torture centre.

“They were racially abused a lot. They suffered verbal harassment, racism,” says Shekh.

All were derided as belonging to the “56 state” a reference to the year Sudan achieved independence and a construct that the RSF guards told inmates they wanted to “destroy”.

Underlining the misery of their situation is the fact that all were seemingly detained for minor, arbitrary reasons.

Most were reportedly detained after preventing RSF troops from looting their homes. Some, says Shekh, were arrested after refusing to hand over their smartphone.

Although all those found in the centre were civilians, during the visit the Guardian also finds several official Sudanese military ID cards among the detritus on the facility’s floor.

Also among the debris were boxes of syringes and discarded packets of prescription drugs, some of which can make users feel lightheaded and drowsy. Military sources believe RSF troops may have used the drugs to numb the monotonous reality of guard duty.

It is a claim underscored by frequent reports of drugged-up RSF fighters as well as a recent discovery eight kilometres south of the torture centre. Several weeks ago, close to Sudan’s main oil refinery, Sudanese army intelligence officers found an industrial-scale factory producing the banned drug Captagon, capable of making 100,000 pills an hour.

Evidence was found that the amphetamine was used locally and smuggled abroad.

The discovery of the RSF torture centre and nearby large-scale Captogan factory raise unfavourable comparisons with Syria, whose former president, Bashar al-Assad, turned his country into the world’s largest narco state.

Similarly, the grisly finds at the military base north of Khartoum appear to be part of a network of RSF torture centres around the capital. Military sources said they had recently found another in southern Khartoum. There, Egyptians were among those tortured, some to death.

As the battle for the capital intensifies and the military – itself accused of myriad war crimes and abuses – posts steady advances against its nemesis, more grisly discoveries are inevitable. Slowly, shockingly, the true scale of Sudan’s terrible secrets will come to light.