By Adam Makary

CAIRO (Reuters) – Like many other residents of Sudan’s capital, painter Yasmeen Abdullah had to leave much behind when she fled the war erupting around her. As an artist, that included most of her work.

“I had to abandon many things but also leave without knowing when I’d return, or if the things I did leave would be there when I got back,” she said.

“About 20 pieces of artwork, years of artistic practice, rough sketches, drawings – literally everything.”

The conflict between rival military factions quickly overran the capital from April 15, trapping civilians amid aerial bombardments, ground battles, marauding paramilitaries and widespread looting.

Abdullah is a member of a youthful art scene that gained momentum from the popular uprising against autocrat Omar al-Bashir and finds itself scattered by war four years later.

She is nine months pregnant, so staying in a city where power has been cut and health services have collapsed would have been especially difficult.

“The health center near my house was bombed the same day I was scheduled for a routine checkup. That’s when my husband and I realised it wasn’t safe to stay,” she said.

Now, she and her husband are taking refuge in Shendi, a city 150km north of Khartoum, where she plans to give birth and then leave Sudan all together.

‘SILENT CRIES’

Under Bashir’s Islamist rule, cultural and social activities were strictly controlled. When he was toppled in 2019, there was a cultural outburst that included street murals and contemporary music.

“We’ve always been repressed, especially during Bashir’s time,” said 28-year-old Rahiem Shadad, who co-founded Downtown Gallery in Sudan’s capital in 2019. “Artists were forced to be in these bubbles, and they had their own silent cries.”

“The revolution changed everything, but mostly, it ushered in a new generation of artists to prominence,” he said.

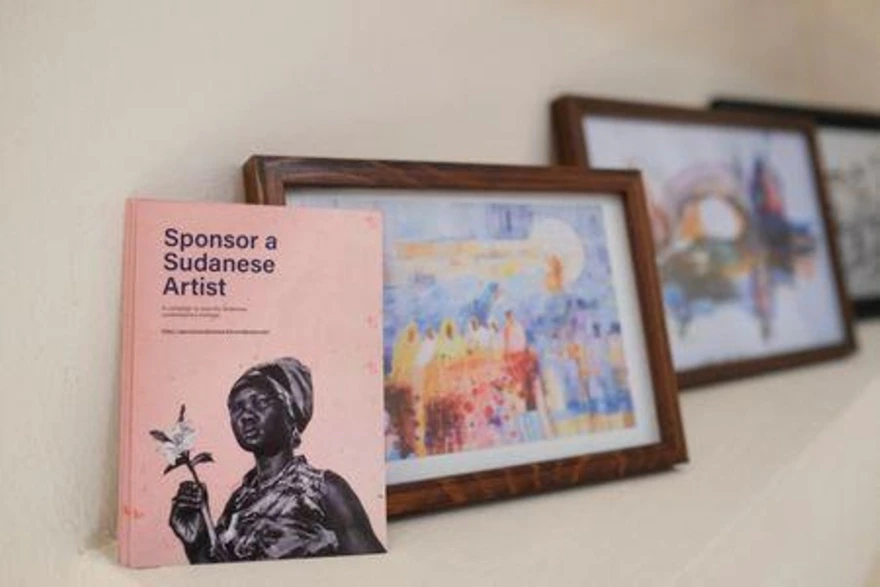

Shadad’s gallery has raised just over $8,500 of a $30,000 target to support artists financially during the war.

One of the 70 people the gallery is helping is Muhammed Yusuf, who refuses to leave his studio in Omdurman, the city across the Nile from Khartoum where he grew up.

“I have my own role as an innovator, as well as my own message to society as a community leader, and this is the place from which I’d like to create,” Yusuf said.

Other artists have dispersed.

Khalid Abdelrahman, known for his stylized paintings of Khartoum neighbourhoods, stayed for a few days in the centre of the city when the war began, before moving his family to the southern outskirts of the capital.

He later made his way to Wadi Halfa, a city 30km from the Egyptian border which he hopes to cross in the coming weeks.

“I need to get the visa to Egypt so I can start working again,” he said.

Painter and retired art professor Salah Abdelhay fled to Egypt with his wife and two daughters. Before leaving, he took some works from their frames, rolled them up and carried them to Cairo. Bigger works were left behind.

“We are afraid for all Sudanese heritage, fine arts, music – everything. These people can destroy everything,” he said.