Paris (AFP) – Territories in Brazil’s fragmented Atlantic Forest where Indigenous peoples enjoy secure land rights have seen measurably less deforestation than similar areas in which land tenure is weak or non-existent, researchers reported Thursday.

The findings, published in the journal PNAS Nexus, are the first to quantify the benefits of enhanced Indigenous land rights for Brazil’s tropical rainforests, and add to a growing body of peer-reviewed literature highlighting more broadly the advantages of Indigenous stewardship.

“Even in highly developed and heavily deforested areas, granting land tenure to Indigenous peoples significantly improved forest outcomes,” including less tree loss and more reforestation, lead author Rayna Benzeev, a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder, told AFP.

“Each year after tenure was formalised, there was, on average, a 0.77 percent increase in forest cover compared to untenured lands,” she added.

“That can add up over decades.”

The Atlantic Forest — Brazil’s second-largest rainforest after the Amazon, stretching along 3,000 kilometres (1,860 miles) of coastline — has been decimated by centuries of urbanisation, agriculture, logging and mining. It is home to 70 percent of the country’s population, including Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Only 12 percent of original forest area remains intact, versus about 80 percent for the Amazon.

Benzeev and colleagues looked at data on changes in forest cover and land tenure in 129 Atlantic Forest indigenous territories between 1985 and 2019.

They compared tree loss and reforestation within territories before and after land rights were granted, as well as across territories with different degrees of land tenure.

“Indigenous lands with tenure showed a reduction in deforestation and increase in reforestation compared to lands that didn’t have secure legal rights,” said Benzeev, writing from Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, where she is sharing her findings with Indigenous leaders.

Jera Poty Mirim, a Guarani leader in the Tenonde Pora Indigenous Territory, said the study confirmed what Indigenous people already knew.

“Even before we reached the final step in obtaining recognition of strong rights to our lands, our people began to take care of our forests and to plant the traditional food crops of the Guarani,” she told journalists this week.

An ongoing challenge

“But wherever communities have secure rights we can protect our forests better and invite partners to support our work to reforest the land destroyed by others.”

On paper, Brazil provides robust legal protections for Indigenous rights. But in reality lax enforcement coupled with corruption has fuelled deforestation and illegal expropriation.

In the Atlantic Forest, encroachment by land grabbers, squatters and extractive industries — whether mining or logging — “remains an ongoing challenge for land defenders”, the report’s authors noted.

Those pressures surged during the administration of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who stepped down on January 1.

Incoming President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has vowed to reverse those trends, and has set 2030 as a target for reaching zero deforestation.

“Titling the lands of Indigenous people is crucial if we want to guarantee the end of deforestation and preserve the global climate in balance,” Paulo Moutinho, a senior scientist at Brazil’s Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) and fellow at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, told AFP, commenting on the study.

The stakes for protecting the Amazon basin, the world’s largest tropical biome, are both local and global.

Climate change coupled with forest destruction are pushing the Amazon basin toward a “tipping point” where it will shift from a tropical forest to a savannah-like state.

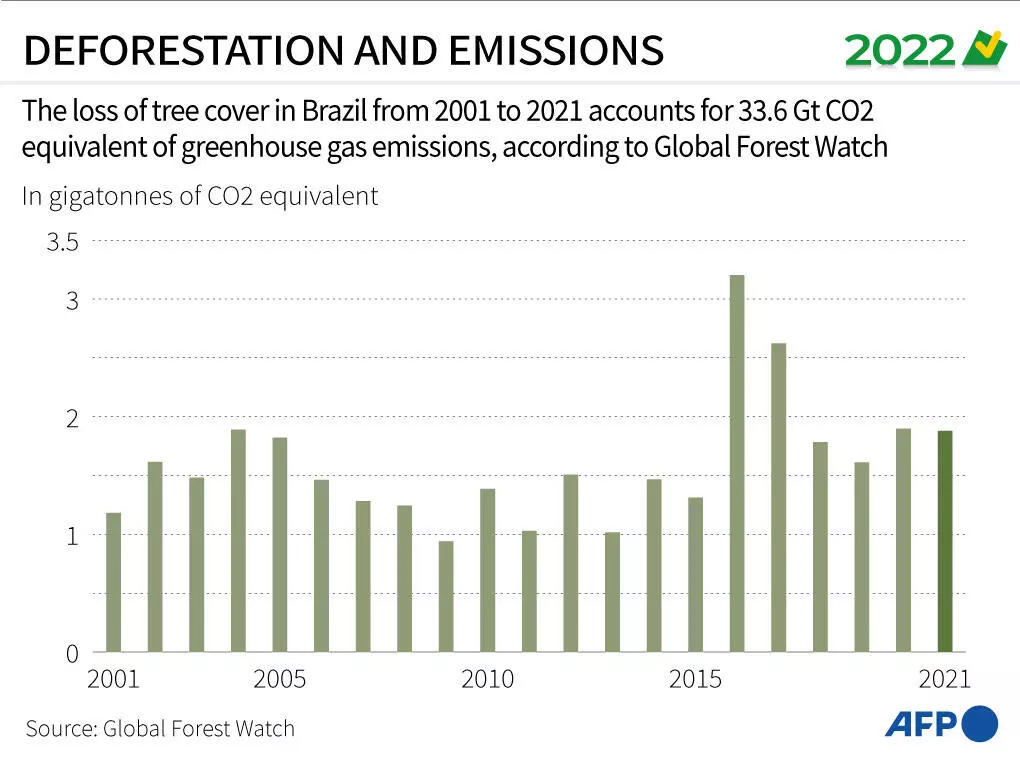

From 2000 to 2020, Brazil experienced a net loss of more than 20 million hectares of forest, or about six percent of total tree cover, according to Global Forest Watch.